Although job vacancies increasingly ask for staff with no ‘9 to 5 mentality’, eight-hour workday is still the norm in the Netherlands. And it has been for one hundred years. Today it is exactly a century ago that the House of Representatives approved eight-hour workday in factories, offices and workshops.

It looks as if not much has changed in that regard, but we have started to work less in the last hundred years, says labor economist Joop Schippers of Utrecht University. “There is much more flexibility than before. More and more employees and self-employed people can determine their working hours. Until the early 60s, we worked six days a week. And now more and more people work 36 hours, so we work less than eight hours on some days.”

Six-hour workday.

Jan de Leede, professor of Human Resource Management at the University of Twente, expresses that working days of six hours ” lead to higher productivity, less stress and less absenteeism. The balance between work and private life is also restored, which is one of the major issues of the current labor market.”

According to historian and journalist Rutger Bregman, there have already been experiments with shorter workweek being done in Sweden. Employees there were indeed less likely to report sick and had less stress. But the costs of the test were high, especially in the public sector. For example, a participating nursing home had to hire extra people to fill in the ‘lost’ hours.

According to Janneke Plantenga, professor of economics at Utrecht University, working fewer hours does not always lead to higher productivity. “In some professions, productivity is linked to attendance, especially in healthcare and education.”

Plantenga says that the discussion in the Netherlands should not only be about working less, but also about more. “Nowhere in the world is the difference of working hours between men and women as big as it is in the Netherlands. Women who work en masse part-time could actually work more hours. Our entire society is geared towards part-time work. Think of school hours and childcare. That actually forces people – and especially women – to work part-time.”

The employers’ organisation VNO-NCW also believes that the challenge for the Netherlands is how we can work more hours in our “part-time culture”. “Shorter working days may sound nice, but due to the shortage and the aging population, this will actually have the opposite effect,” says a spokesperson. “Extra hands in healthcare and education are already difficult to find, let alone if people start working less.”

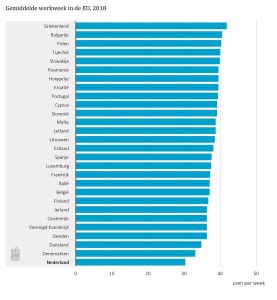

Figures from the CBS show that on average the Dutch – including the working hours of part-timers – have the shortest working week in Europe (and probably in the world).

Nevertheless, De Leede remains in favor of working less. “I see the objections, but I call for more experiments. If the full-time standard for everyone goes down, there can be more equilibrium between men and women. Not only in the labor market, but also in the distribution of possible care duties. ”

Labor economist Schippers sees that the full-time standard is going down. “It may well be that we see a 32-hour workweek as the standard in 20 years. The development towards fewer working hours fits in with a movement that has been going on for much longer. With increasing prosperity we spend more on consumer goods and we want more free time. That has been going on since the second half of the nineteenth century. First, children up to a certain age were exempt from work, then the elderly and then we start cutting the work hours. That movement just continues. ”

Source: Nos.nl

Recent Comments